1916: A Bronze Memorial Tablet

By Sculptor Martha M. Hovenden

In First Reformed Church, Lancaster

Above: Martha M. Hovenden while studying at Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts. Image source: PAFA

Above: The bronze tablet on the rear wall of the church sanctuary. With portraits of Ulrich Zwingli and Michael Schlatter.

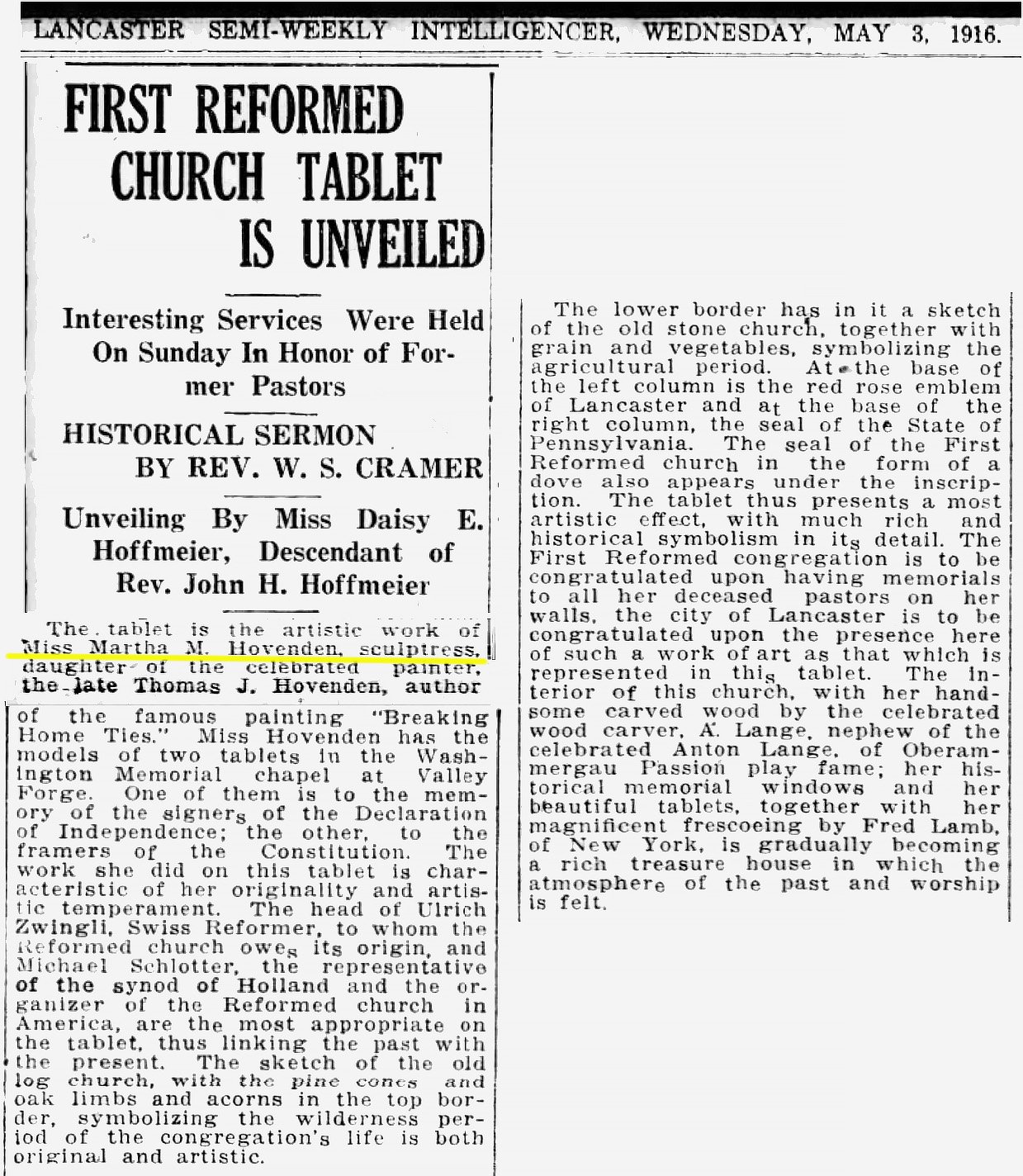

Numerous memorial tablets line the walls of First Reformed Church to commemorate former pastors. One of the most distinctive memorials there is this bronze bas-relief tablet created by a talented sculptor from Montgomery County: Martha M. Hovenden.

The tablet is prominently displayed on the sanctuary’s rear wall. It displays the names of pastors who served the congregation from 1732 to 1850. Martha created this table by modeling it in clay and then casting it in bronze at the Roman Bronze Work of Brooklyn, NY.

In addition to the two portraits, the tablet also depicts the log church and the stone church which preceded today’s brick church building.

1928: Martha’s Tablet Published by the Dean of Yale’s Divinity School

Rev. Dr. Luther A. Weigle:

Above: Rev. Luther A. Weigle, Dean of Yale Divinity School, and the photo of Martha Hovenden’s tablet in his 1928 book. Image source left: Yale University, right: Google Books.

Apparently Rev. Luther Weigle appreciated Martha Hovenden’s memorial tablet. He was dean of the Yale Divinity School from 1928 to 1949. He spoke at Lancaster’s First Reformed Church as a visiting pastor on numerous occasions. He admired Martha’s tablet.

In 1928 Yale University Press published Rev. Weigle’s book American Idealism. In that book he included information about Michael Schlatter. He used a photo of Martha’s bronze tablet to illustrate that text (photo above). Meanwhile, during Rev. Weigle’s tenure at Yale the seminary admitted women for the first time, in 1932. During that same time Rev. Weigle chaired the committee that produced the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

Elsewhere: Two Sculpted Tablets by Martha Hovenden

In Washington Chapel, Valley Forge Park:

Above and below: Martha Hovenden’s 1936 limestone panel was commissioned by the Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge Park to honor the framers of the U. S. Constitution. Ten years earlier, in 1926, she had completed her first panel here, located on the opposite side of the sanctuary. That panel commemorates the Declaration of Independence.

The chapel is filled with stained-glass windows by the studio of Nicola D’Ascenzo, who also created three windows for Lancaster’s First Reformed Church. The chancel window above is D’Ascenzo’s Martha Washington window, installed in 1918. These two tablets at Valley Forge are Martha Hovenden’s best-known works.

Previously in 1911:

Martha Hovenden in a 1910 Catalog of Medals:

Above: Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Contemporary Medals,

The American Numismatic Society, March, 1910

Martha Hovenden’s Home and Studio was

A Landmark of the Underground Railroad

Her Grandparents were Quaker Anti-Slavery Abolitionists:

Above left: Martha Hovenden’s home on her parents’ farmstead in Plymouth Meeting, Montgomery County. Above right: Martha’s studio was also known as Abolition Hall because it was used by her Quaker grandparents as an anti-slavery lecture hall. Images source: Plymouth & Whitemarsh Twp, Arcadia.

The Quaker village of Plymouth Meeting was a hotspot of anti-slavery activism. Martha’s grandparents, Martha and George Corson, led a fight to end slavery while living there on their ancestral farmstead. Martha later lived on this homestead most of her life.

In 1831 Martha’s grandparents co-founded the Plymouth Meeting Anti-Slavery Society. The group initally met at the Plymouth Friends Meeting House, located across the street from this home. Martha’s grandparents also co-founded the Montgomery County Anti-Slavery Society a few years later.

George and Martha Corson turned this homestead into an important station on the Underground Railroad. They provided food and shelter to hundreds of escaped slaves. They added a second floor to their carriage building for an assembly hall to host anti-slavery lectures. That building later became the art studio of Martha’s artist parents. She also used the building for her own studio.

Anti-Slavery Leaders who Spoke in Martha’s Studio

When it was her Grandparents’ Abolition Hall:

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, Lucretia Mott, etc.

Above left to right: Anti-slavery activists Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, Lucretia Mott. Images source: Wikimedia

Martha’s Parents later used Abolition Hall for their art studio.

Martha then used it for her studio.

Above: Historical marker at Martha Hovenden’s home and studio. She and her parents converted Abolition Hall into an art studio. Martha created the memorial tablet for First Reformed Church here in Abolition Hall.

Martha Hovenden’s Parents:

Nationally renowned artists Thomas Hovenden and Helen Corson Hovenden:

Above: Martha’s parents: Thomas Hovenden and Helen Corson Hovenden. Image source: Historical Society of Montgomery County

Martha Hovenden’s father, Thomas Hovenden, was one of the most celebrated American genre painter of his era. He was born in County Cork, Ireland, and became an orphan at age six during the Potato Famine. He emigrated to the U. S. when he was 23 after studying art at the Cork School of Design.

Thomas Hovenden married artist Helen Corson. The couple moved to her family’s homestead in Plymouth Meeting, Montgomery County. Helen Corson’s abolitionist parents had used this home as a safe house in the Underground Railroad, and coverted the carriage building into Abolition Hall. The Hovendens used that building for their art studio, as did their daughter Martha Hovenden.

Thomas Hovenden’s Most Famous Paintings:

Breaking Home Ties (1890) and The Last Moments of John Brown (1884)

Above: Breaking Home Ties by Thomas Hovenden. Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Thomas Hovenden’s painting, Breaking Home Ties, was one of the most acclaimed American genre paintings of its era. It was the most popular painting exhibited at the 1893 Columbian World’s Fair in Chicago. By the late 1890s reproduction prints of this painting appeared in thousands of homes.

Above: The Last Moments of John Brown, by Thomas Hovenden. Image source: Wikimedia.

John Hovenden painted this portrait of John Brown, the controversial abolitionist. He had led a failed attempt to capture weapons for a slave revolt in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. The painting depicts him on the way to his execution.

John Hovenden was an art professor at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. His students included Alexander Stirling Calder and Robert Henri. Hovenden is also remembered for his numerous paintings of Black families who were his neighbors in Montgomery County. Those neighbors lived near his studio at his family’s Abolition Hall Homestead, where his parents had been tireless conductors on the Underground Railroad.

A Portrait of Two-Year-Old Martha Hovenden

Painted by her mother Helen Corson Hovenden:

Above: Martha Hovenden and her dog Rob, painted by her mother Helen Corson Hovenden. Image source: Woodmere Art Museum.

Above: In 1888 artist Helen Corson Hovenden painted this portrait of her daughter, the future sculptor Martha Hovenden. Mother and daughter both lived much of the lives on the Corson / Hovenden Homestead, site of Abolition Hall. They both used the the former Abolition Hall for their art studio, as did Helen’s husband Thomas Hovenden.

The homestead is now preserved as a historic site by Whitemarsh Township and the Whitemarsh Art Center because its important history of abolition and American art.

Martha Hovenden never married. She lived most of her life here on her family’s homestead at Abolition Hall. Her work survives her, like a sculpted memorial to her life.

Return to this website’s index page about First Reformed UCC Church: Index page / Home