Historic Floor Tiles by Henry Mercer

in St. James Episcopal Church, Lancaster

St. James’ chancel has two important installations of Mercer tiles. The best-known tiles here are Mercer’s Bible in Tile series of wall tiles, installed in 1916. Those sculptural panels depict Bible stories. The tiles in those panels are based on biblical scenes that Mercer found on antique Pennsylvania stoves.

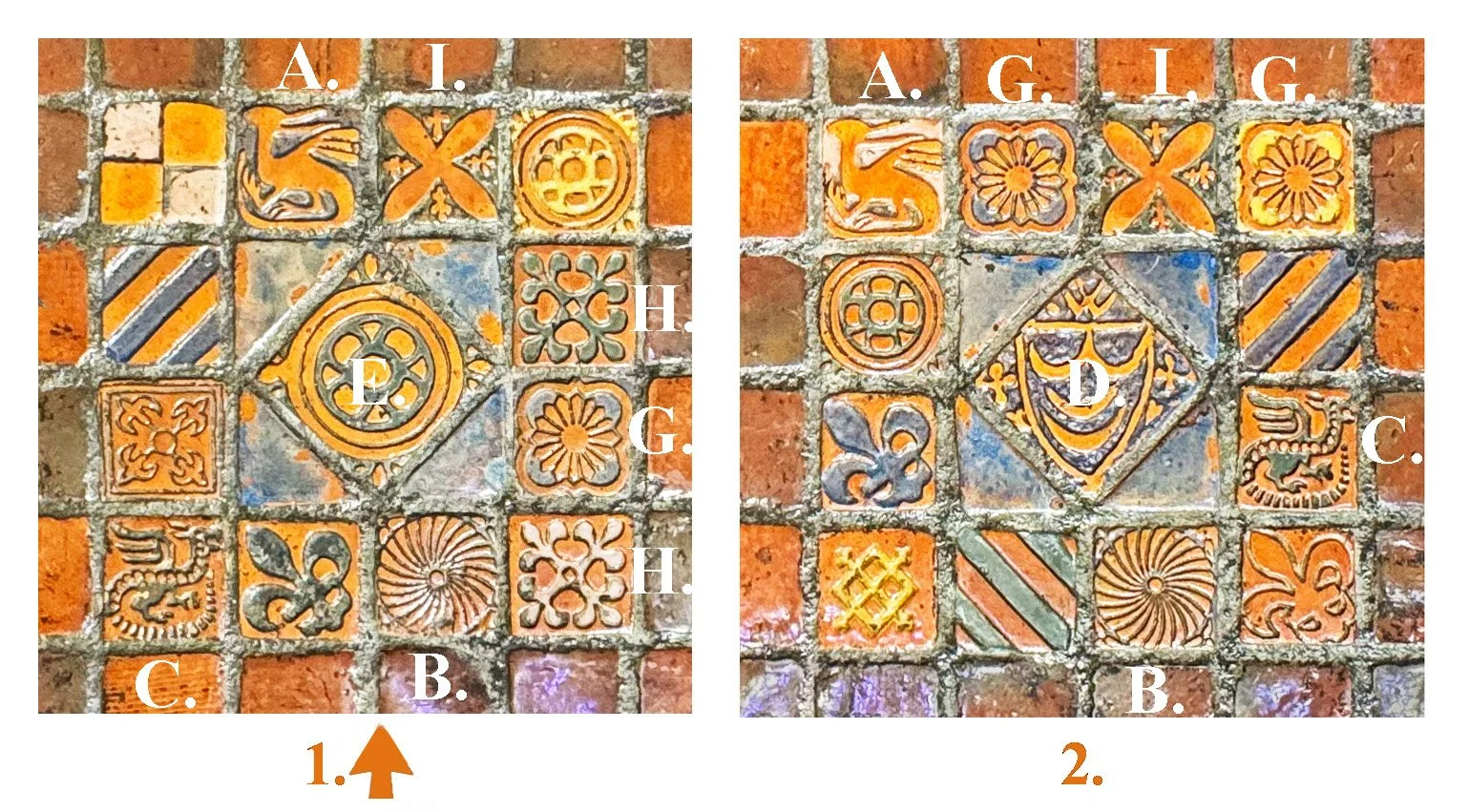

The church’s second Mercer-tile installation is shown here on this page. These are the chancel’s paving tiles which were set in 1927. Included in this group are four squares of decorative tiles which Mercer designed after studying historic tiles from medieval churches and monasteries of England and elsewhere.

The Chancel Floor’s Mercer Tiles

Based on Historic Tiles from Medieval Churches:

Henry Mercer’s “Heirlooms from Ecclesiastical Floors”:

Henry Mercer designed these earthenware tiles after extensive travel throughout Britain and elsewhere in Europe to research historic tiles. For this floor he created checkered groups of historic designs surrounded by pavements of plain squares (quarries). He described these Medieval Revival tiles in the 1913 catalog of his Doylestown tile works as “heirlooms from ecclesiastical floors.”

Above: Tiles based on designs of medieval England and Normandy. Henry Mercer’s names for these tiles:

A. Dragon of Castle Acre Priory B. Circle of Castle Acre Priory C. Scaled Dragon of Castle Acre Priory D. Crescent Arms of Castle Acre Priory E. Petals in Double Circle F. Crossed Squares of Eweline, Oxfordshire G. Wheel of Bayeux Normandy H. Quatrefoil of Jervaulx Abbey, Yorkshire I. Quatrefoil and Flowerets of Ecclesiological Society Collection. Other tiles in these groupings are based on historic tiles from other regions, including ancient Persia.

St. James’ Mercer Tiles

Which are Based on Tiles from England’s Castle Acre Priory:

Priory image source: English-heritage.org.uk

“Mercer was the first modern tile maker to produce half-glazed decorative floor tiles.” (Quote: text in an exhibit at Mercer’s Doylestown tile works.)

Henry Mercer was intrigued by a group of medieval tiles found at Castle Acre Priory, in Norfolk, England. The tiles were made in the late 1300s at the Bawsey kiln. Those medieval tiles had originally been fully glazed. Mercer noticed that after centuries of foot wear the glaze on the tiles’ raised surfaces was worn away, exposing the red clay body. The glaze color in the tiles’ recessed areas remain intact.

This observation changed Mercer’s tile making. He realized he could simulate the effect of age and wear by wiping off the glaze from his tiles’ raised surfaces before kiln firing them. This technique created the illusion of centuries of wear for his new tiles. Mercer invented this “half-glazed” effect, and used it on countless tiles, including these floor tiles at St. James.

A Mercer Tile Design on St. James’ Chancel Floor

From the Jervaulx Abbey in North Yorkshire, England:

Abbey image source: Jervaulx Abbey Facebook

Above: Henry Mercer named this tile design in his 1913 tile-works catalog as Quatrefoil of Jervaulx Abbey, Yorkshire. This monastery was the home of Cistertian monks who previously were in Burgundy. This design appears several times in the St. James chancel floor.

Henry Mercer found Inspiration for these Medieval Tile Designs

From his Research at the British Museum:

Image source: Travel.USnews.com

In the early 1900s Henry Mercer travelled to Europe to find historical designs for his tiles. He was already using decorations from antique Pennsylvania German stoves for some of his tile designs. Another important influence on his designs was his new appreciation for medieval tiles.

In London’s British Museum Mercer received full access to study the museum’s collection of English medieval paving tiles. The museum has tiles from ruined churches and abbeys throughout Britain. Mercer sketched the tiles, took notes about their colors, and made wax impressions of some examples.

Mercer returned to Pennsylvania and incorporated those medieval designs into handcrafted pavings of a type previously unknown in America.

Medieval Tiles from the British Museum

Influenced Many Mercer Tiles at St James:

Above left: British Museum’s tiles from a Norfolk monastery, the Castle Acre Priory. Henry Mercer sudied these tiles at the museum in the early 1900s. Image source: British Museum

Above right: Mercer’s tile at St James that he titled Circle of Castle Acre Priory

“Mercer’s medieval pavings were strikingly different from any others made in the United States, not only in their designs but also in the chance effects resulting from hand fabrication. These irregularities in his tiles annoyed many tile contractors who were accustomed to working with machine-made tiles of highly precise, standard dimensions and colors.”

“Tile setters tried in vain to make absolutely level pavements from his tiles, but most learned soon enough to appreciate the subtle effects of the minute risings and fallings of the surfaces they installed.” (Quote: Henry Chapman Mercer and the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, Cleota Reed, 1980.

Henry Mercer also Installed these Medieval Revival Tiles

In his Dining Room in Doylestown:

Above: A museum-board portrait of Henry Mercer stands by the fireplace in his castlelike home named Fonthill Castle. Mercer donated this home, his collections, and his Mercer Museum to the Bucks County Historical Society. He created this room to be his dining room / salon. He named this room “The Saloon.”

A primary entertaining room, such as this room, would typically have been called the “salon”, not the “saloon”. Apparently Mercer thought the name “salon” was too formal for his home, too bourgeois. Mercer was filling his home and his museum with historic, everyday objects made by everyday people. Salon society was not his focus. He was interested in the history of workers, artisans, and craftspeople.

Tiles by Henry Mercer in his Dining Room

Some of these Tiles also Appear in St. James’ Chancel Paving:

Above: Tiles by Henry Mercer in his home’s dining room, inspired by medieval tiles.

Above: Tiles by Henry Mercer in his home’s dining room, inspired by medieval tiles.

Tiles by Henry Mercer in his Home

Based on Medieval Tiles of England and Wales:

Above: Name of the tiles in Mercer’s tile catalog of 1913:

Tile 1: Foliate Circle of Castle Acre Priory Tile 2: Vicar of Stowe of Castle Acre Priory - “Pray for the Soul of Father Nicholas, of Stowe, Vicar.” Tile 3: Crossed Lozenge of St. Cross, Hampshire Tile 4: Birds of Tintern Abbey also Beaulieu Abbey Tile 5: Triangles of St. Benet. Westminster Abbey

Above: Tintern Abbey ruins, and tile named Birds of Tintern Abbey in the floor of Henry Mercer’s dining room. Based on a medieval tile from Tintern Abbey, Wales. Abbey image source: Wikipedia

The Mercer Floor Tiles at St. James

Were Funded by Miss Mary Muhlenberg:

The Mercer tiles of St. James’ chancel floor were funded by Miss Mary Elizabeth Muhlenberg (1853 - 1929). She was a Lancaster resident her entire life. She had a career in nursing and never married. Mary Muhlenberg was active in all branches of church work at St. James. She taught Sunday School, and was with the Women’s Auxiliary and the King’s Daughters. She also worked with the Community Service Association.

The Muhlenbergs were one of the most prominent Pennsylvania German families in Lancaster. Mary Muhlenberg’s great grandfather was Rev. Dr. Henry E. Muhlenberg, pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church and first president of Franklin College, now F&M College. Mary Muhlenberg was a cousin of a former pastor of St. James Episcopal Church: Rev. Dr. William A. Muhlenberg, who was co-rector of St. James from 1820 to 1826.

Above: 1927 newspaper describes these tiles being installed